Filtering out indoor air pollution is the highest leverage one-time health intervention

Credit for doing good research on air quality and blogging about it goes to Dynomight, I just want to boost their ideas. You should read the original post, but a brief summary of the problem it presents is: when you breathe in tiny particles, they make you more likely to get cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other things you don’t want. Dynomight looks at several countries, and if you’re in India or China, you really, really need to get an air filter, because ambient air pollution is the single most impactful factor they found for increasing your lifespan. But I’m in the US - am I OK? Sort of - cities in the US are less polluted than cities in India and China, but Dynomight still finds that if I’m not on drugs or drinking, air pollution is second only to high BMI as a health risk (as measured by disability-adjusted life-years per year).

Fortunately, PM2.5 sensors are pretty cheap, so I got one on Amazon and took some measurements. I initially got very bad news: the ambient indoor PM2.5 readings were on par with some of the world’s most polluted cities! Fortunately, a friend pointed out that this was probably a mistake, and I realized that I had misread the sensor’s spec. I fixed the problem and found that the indoor air quality in my apartment was pretty good! But Dynomight finds a pretty consistent linear relationship between DALY (disability-adjusted life-year) deficit and air pollution even at low levels, so I bought an air filter. As Dynomight points out, this is a ridiculously high-leverage intervention: it’s pretty much guaranteed to improve air quality, and it sure looks like that will extend your life. By how much? My apartment had a baseline level of 8 ug/m^3. Dynomight gives two useful ways to measure effect of PM2.5 exposure:

- You lose 1 additional hour of DALY per hour exposed to PM2.5 levels of 2500 ug/m^3

- You lose 1 DALY over your lifetime if your average PM2.5 exposure is 33.3 ug/m^3.

Let’s say I spend around 16 hours a day in my apartment (this, sadly, is probably an underestimate). Over the course of a year, I expect to lose 16 * 365 * 8 / 2500 = 18 life-hours as a result of this exposure level. Over my lifetime, this means I can hope to lose something like a month and a half off my lifespan due to indoor air pollution, assuming I never move. Or I can buy this back for less than $100. This is why the air filter is so ridiculously worth the expense. I got the IKEA Fornuftig filter, which is extraordinarily quiet on its lowest setting and reduced the PM2.5 count to zero on my sensor. Nice!

Cooking

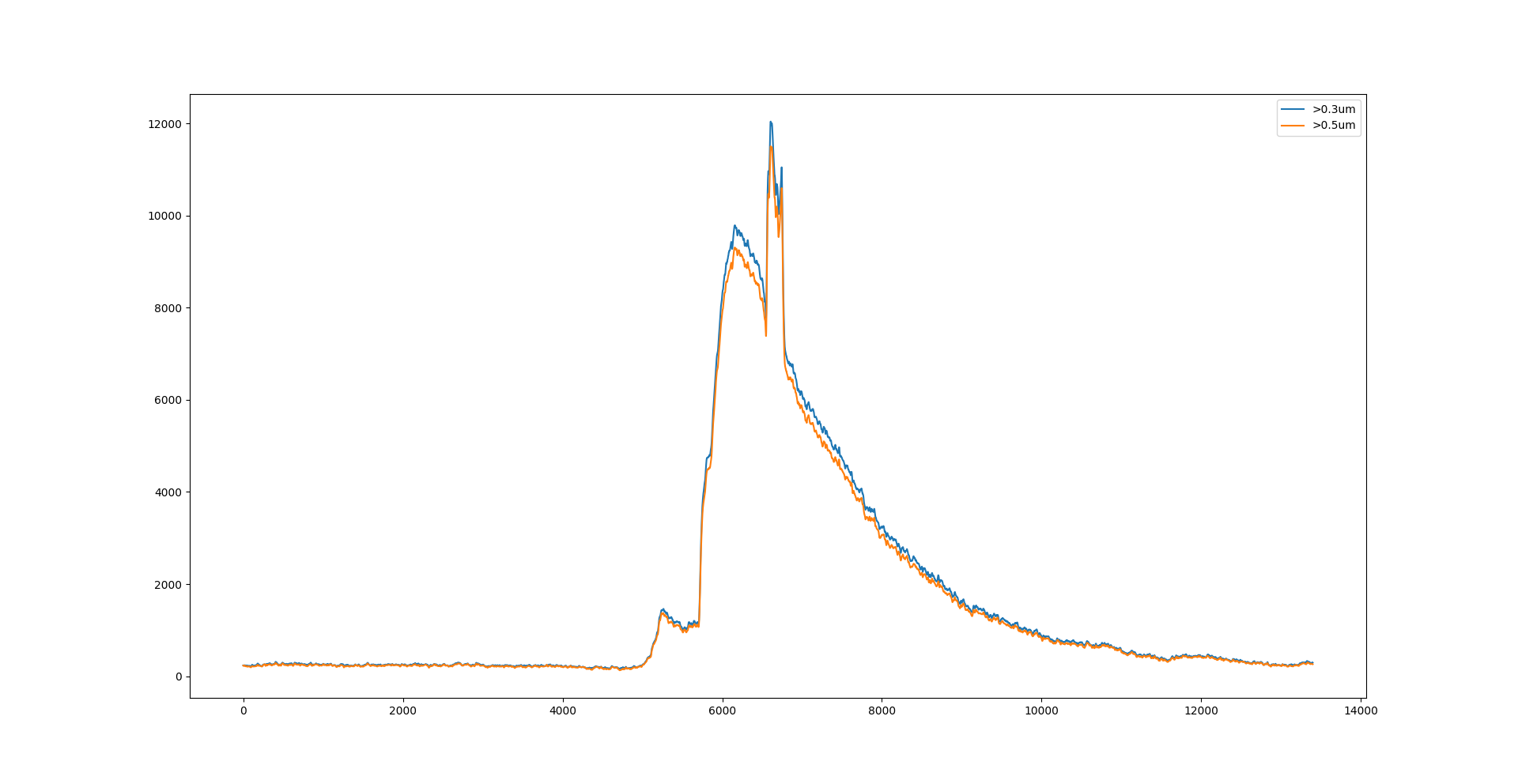

Unfortunately, that wasn’t all I learned from my sensor. See, I thought it would be pretty slick to get it to to a live plot of the raw particle counts. So I set it running, did some work, and made dinner.

Ah, shit

In order, here is what happens in the graph: the relatively small bump is me as I start cooking. The huge spike comes from me opening the door to my office. Then I turned my filter all the way up and it starts to decay, but I get curious and bring the sensor into the kitchen, where the particle count achieves its maximum value. I then bring the sensor back to the office and close the door. Please note that the y-axis here is RAW COUNTS, NOT ug/m^3, so the graph isn’t as bad as it looks. The value in ug/m^3 in the kitchen was around 500 though, so still quite bad, and it took 3 hours to come down to normal. I estimate that cooking dinner cost me something like 20 life-minutes (from pollution - it would be weird, though not inaccurate, to add the time I spent cooking to this). I should note here that I was frying tofu, which produces more smoke than most cooking, but this is potentially very significant! Cooking dinner was equivalent to several days of ambient indoor air pollution. If I cooked like this every night, I would lose 5 life-days a year purely from the particulate matter.

This is interesting because it suggests that indoor air pollution follows a Pareto distribution - in this case, before the filter, 81% of the particles I inhaled each day came from 12.5% of the time (the three hours following whenever I start to cook). Malcom Gladwell has a good piece somewhere on Pareto problems (he calls them “long-tail problems”), where he suggests that any time you see a Pareto problem, you’re lucky, because you can basically concentrate all of your efforts in one place and get significant results for (hopefully) a fraction of what solving the entire problem would cost you. The obvious solution to generating too much PM while cooking is to cook outside as much as possible, perhaps wearing a mask when you have to stand right over the grill. Failing that, I ran a very informal experiment with my microwave fume hood (mounted right above the stovetop). Dynomight helpfully informs us that Kang et. al. tried the fume hood on its own and found an 86% reduction in peak PM2.5! I observed similar effects: when I cooked again the next night, I used the fume hood and particle count was down >90% (although I was cooking something different and less smoky, so there’s a confounding variable here).

Final thoughts

- Unless you have excellent reason to believe that your indoor air isn’t polluted, a PM2.5 sensor and air filter are ridiculously well-worth the investment. A filter is probably the most effective one-off intervention you can perform to improve your healthspan.

- Regardless of whether you get a filter, you can improve your health significantly by using the fume hood above your stove while cooking, if you have one.